Overview

Ankylosing Spondylitis is an autoimmune disease which causes back pain and stiffness. It most commonly occurs in young men, but men and women of any age can have Ankylosing Spondylitis. While there is no cure, treatment options for Ankylosing Spondylitis have improved over the last few years with good therapeutic options available.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Ankylosing Spondylitis?

- Most people with Ankylosing Spondylitis, or AS, complain of lower back pain and stiffness, caused by inflammation. However, AS can affect any part of the spine, including the neck, upper and middle back.

How common is Ankylosing Spondylitis?

- AS is not a common disease, with less than 1% of the population having a diagnosis. It is more common in men than women, with the first manifestations often occuring as a young adult.

Could I have prevented AS? Why does Ankylosing Spondylitis happen?

- Because we do not fully understand why AS happens, there is nothing we know that could prevent it.

- The exact cause of AS remains unknown. It is possible an unidentified trigger initiates the immunologic process which causes inflammation.

- A number of different genetic markers have now been identified which increase the risk of developing AS, although no one marker completely explains the cause.

I heard something called HLA B27 causes Ankylosing Spondylitis?

- HLA B27 is a genetic marker found in approximately 8% of the general caucasian population.

- While most people with HLA B27 DO NOT have AS, most people with AS are B27 positive.

What are the common symptoms of Ankylosing Spondylitis?

- Ankylosing Spondylitis causes “inflammatory back pain”. Unlike regular back pain which affects the lower back and is best first thing in the morning and worse with activity, inflammatory back pain is associated with back stiffness in the morning, often lasting at least 1 hour, and improves with activity. It most often involves the lower back, but can affect the entire spine.

How is Ankylosing Spondylitis diagnosed?

- Your physician will listen closely to your history of back pain and for any other clues that may suggest you have AS. If diagnosed early, there may be no findings on clinical exam, although many patients have difficulty moving their back through a full range of motion.

Are there any tests to confirm Ankylosing Spondylitis?

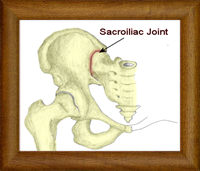

- The most common test is an X-ray of the sacroiliac joints in the hip, as this area is most often involved. However, if caught very early, there may be no X-rays changes yet. If your doctor still suspects AS, they may arrange an MRI of your sacroiliac joints, as an MRI can detect early signs of inflammation before they are seen on a X-ray.

- Your physician may order certain blood tests to look for inflammation and rule out other diagnostic possibilities, but none of these are specific.

- Because HLA B27 is so common in the general population, it cannot diagnose AS. Therefore, it is not necessary for most patients.

Besides my back, can AS affect any other joints?

- AS can also involve other large joints including the shoulders, hips, and knees. Chest involvement is also described. A minority of patients will have smaller joints affected too.

Does AS only affect joints?

- The attachment between tendons or ligaments to bone can also become inflamed and cause pain. Common examples include the Achilles tendon in the ankle, the plantar fascia on the bottom of the heal, and the patellar tendon at the knee.

- There are a number of other diseases which are commonly associated with Ankylosing Spondylitis and may give your physician a clue that your back pain is from an inflammatory cause. Common examples include inflammation of the eye, called uveitis, psoriasis, and Crohn’s Disease or Ulcerative Colitis.

- Other organ involvement can also occur, although less common, including heart, lungs, and kidneys.

Is there a cure for Ankylosing Spondylitis?

- There is still no cure for AS, but treatment options are improving, with a majority of patients having good results and able to live their lives normally.

How is AS treated?

-

There is no cure for axSpA, but treatment aims to:

- Relieve pain and stiffness in the back and affected areas.

- Keep your spine straight.

- Prevent joint and organ damage.

- Preserve joint function and mobility.

- Improve quality of life.

Early, aggressive treatment is the key to preventing long-term complications and joint damage. A well-rounded treatment plan includes medication, nondrug therapies, healthy lifestyle habits and rarely, surgery.

Medications

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NSAIDs are the most commonly used drugs to treat axSpA and help relieve pain. They include over-the-counter drugs, such as ibuprofen (Advil) and naproxen (Aleve), as well as the prescription drugs indomethacin, diclofenac or celecoxib.

- Analgesics. In addition to NSAIDs, the doctor may recommend acetaminophen (Tylenol) for pain relief.

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Conventional DMARDs are not usually used in people with axSpA that effects just the back. Sulfasalazine, however, may be used for joints other than those in the back and pelvis.

- Biologics. A type of DMARD, biologics target certain proteins and processes in the body to control disease. Biologics are self-injected or given by infusion at a doctor’s office. The ones that work best for axSpA are tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors and interleukin (IL-17) inhibitors.

- Corticosteroids. These powerful drugs are not often used for spinal disease in axSpA. However, injecting steroids into a knee or shoulder can provide quick relief.

Exercise

Regular physical activity is a critical part of managing axSpA. It helps prevent stiffness and preserves range of motion in the neck and back. Walking, swimming, yoga and tai chi can help with flexibility and posture. It’s also important to strengthen your core and legs. Talk to a physical therapist to put together a total exercise plan.Physical Therapy and Assistive Devices

A physical therapist will teach you to strengthen and stretch your muscles to help keep you mobile and reduce your pain. Occupational therapists can prescribe assistive devices and give tips for protecting joints and making daily tasks easier.Surgery

Most people with axSpA will never need surgery. But joint replacement can help people with severe pain or joint damage. Surgery may also help straighten a severely bent forward spine. Self Care Eat a healthy diet. There’s no special diet for axSpA. But, eating anti-inflammatory foods, like the ones found in the Mediterranean dietmay help. Eat plenty of fatty fish, fruits, vegetables, whole grains and extra virgin olive oil. Limit red meat, sugar, and processed foods.

Avoid smoking. Smoking worsens overall health, and it can speed up disease activity and joint damage. It can also make it harder to breathe. Talk to your doctor about ways to help you quit.

Practice good posture. Good posture can help ease pain and stiffness. Adjust the height of the computer monitor or desk so the screen is at eye level. Plant your feet firmly on the ground. Avoid staying in cramped or bent positions. Alternate between standing and sitting, and use a cushion to support your back. Be careful of “texting neck” when cellphone use is constant.

Stretch. Stretching exercises, especially after a warm bath or shower, can help ease pain and relieve stiffness.

7 Dynamic Warm Ups

Dynamic stretches can increase flexibility, help you warm up and protect you from injury before you work out.

By Linda MeloneHitting a golf ball or jumping into a vigorous game of tennis without an adequate warm up or stretch increases the risk of injury. While traditional static stretching (stretch-and-hold) helps flexibility, it isn’t a warm-up in itself. The solution is a dynamic warm up that uses compound movements – essentially moving the body while you stretch.

“Warm-ups that simulate moves you’ll be performing during the workout work best,” says Amy Ashmore, PhD, exercise physiologist with the American Council on Exercise (ACE). “The key to using dynamic warm-ups for those with arthritis lies in using a smaller range of motion and staying within your abilities.” For example, perform a modified squat (half way) versus a full squat.Dynamic Stretching Tips

Try these seven dynamic stretches that can help you warm up before your next workout.Dynamic Stretching Tips

1. Hip Circles

Stand on one leg, using a countertop for support, and gently swing the opposite leg in circles out to the side. Perform 20 circles in each direction. Switch legs. Progressively increase the size of the circles as you become more flexible.

2. Arm Circles

Stand with feet shoulder-width apart and hold arms out to the sides, palms down, at shoulder height. Gently perform 20 circles in each direction. Progressively increase the size of the circles as you become more flexible.

3. Arm Swings

Stand with arms out in front, parallel to the floor, palms facing down. Walk forward as you swing arms in unison to the right so your left arm is in front of your chest and fingers point out to the right. Keep torso and head facing forward – only move at the shoulder joints. Reverse the direction of the swing (as you keep walking) to the opposite side. Repeat five times on each side.

4. High-Stepping

Stand with feet parallel to each other and at shoulder-width apart. Step forward with the left leg and raise the right knee high up toward your chest (use a wall for balance, if needed) and use both hands (or one, if using the other for balance) to pull the knee up farther. Pause and bring right leg back down; repeat with the other side and continue “high-stepping” five times on each leg as you walk forward.

5. Heel-to-Toe Walk

Stand with feet shoulder-width apart and take a small step forward by placing the heel of the right foot on the ground and rolling forward onto the ball of your foot, rising as high as possible (as if standing on tip-toe), while bringing the left foot forward and stepping in the same heel-to-toe roll. Repeat five times on each leg.

6. Lunges with a Twist

Stand with feet parallel to each other and take an exaggerated step forward (keep one hand on a wall for balance, if needed) with your right foot, planting it fully on the floor in front of you, allowing the knee and hip to bend slowly; keep torso upright. Keep right knee directly over ankle – do not allow it to pitch forward over your foot. Slightly flex your left knee as you lower it toward the ground until it is a couple inches above the floor (or as far as flexibility allows). In this position, reach overhead (skip the overhead reach if you’ve recently had shoulder surgery) with your left arm and bending torso toward the right side, return to upright and step forward with the left foot. Repeat five times on each side.

Note: Do not attempt if you have trouble with balance.

7. Step Up and Over

Stand with feet shoulder-width apart, hands on hips (or lightly touching a wall in front of you for balance). Shift weight to your left leg as you lift your right leg until thigh is parallel to the ground and then step out to the side as if stepping over an object; pause and lower into a squat (or half squat). Pushing up through the heels, stand up and return leg to starting position. Repeat five times on each side.

Pace yourself. On tough days, pace your activities and take short breaks throughout the day to manage fatigue.

What It Really Means to “Pace Yourself”

You’ve likely heard that you need to “pace yourself ” to help manage your arthritis condition and its symptoms. But what does that mean, exactly?

“The general idea is to plan for a ‘just right’ amount of activity, balanced with mini rejuvenating breaks,” says Stacey Schepens Niemiec, PhD, assistant professor of research in the Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “The aim is threefold: preventing symptoms from limiting what you can do; reducing the need for long periods of inactivity that come after overdoing it; and, ultimately, increasing function.”

Pacing isn’t always about avoiding doing too much. It’s also about staying out of a cycle of doing too little, stresses Anna L. Kratz, PhD, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“Figuring out how to stay physically active is one of the cornerstones to aging well with arthritis,” says Kratz. “Pacing is one way to plan and moderate activity so the timing and intensity work for you.”

Experimenting and Setting Expectations

Learn how much you can do on both “good” and “bad” days without flaring symptoms. Give yourself time to figure it out and don’t compare yourself with others – or with what you could do before arthritis. With a chronic condition you may never be 100% pain-free. Pacing can’t eliminate pain, but can help you stop before pain gets out of control.

Self-awareness

“You have to recognize patterns to address them,” says Niemiec. “Try keeping a diary to track your activities and subsequent arthritis symptoms for a couple weeks.” It’s not just physical activities like yardwork or exercise that can flare symptoms, says Kratz. “Oftentimes, things like dealing with the stress of a toxic person or a long call with a credit card company that lead to the most exhaustion and pain,” she says.

Prioritizing

Make space for the activities most important to you and let go of less meaningful ones. “When you have arthritis, you need to prioritize your health in a new way,” says Kratz. “This can be hard because it can get at the core of how you see yourself – someone who keeps a spotless house or is always on the go, for example.”

Planning

Making a plan – rather than reacting to symptoms – is the foundation of pacing, says Douglas Cane, PhD, a clinical psychologist specializing in pain management at the Nova Scotia Health Authority in Canada. Think about how a given activity will affect you, and make a plan that’s likely to get you through it without causing a flare. Planning may include choosing your “best” time of day to tackle a stressful task or making sure you get good sleep and nutrition in the days before an important event.

Consistency and Repetition

Things aren’t going to be a lot better tomorrow just because you paced well today, says Cane. “Doing it consistently for months – not days or weeks – may allow people to gradually increase their overall functioning.” Niemiec stresses that activity pacing takes practice, motivation and perseverance. “It’s OK to experience setbacks. In fact, they are inevitable,” she says. “The trick is to pick yourself up and try again.”