On the Canada-China Economic Complimentarities Study Part I

In the wake of the announcement of Canada’s participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership talks spearheaded by the Americans, media focus has been on Canada’s role in what many feel will be a lumbering process. Then, a couple days ago, Canadian Trade Minister Ed Fast released the landmark “Canada-China Economic complementarities Study” jointly with Chinese Commerce Minister Chen Deming.

Begun last year at the behest of Prime Minister Harper and Chinese President Hu Jintao, the study covers seven key sectors with strong complementarities but also distinct challenges. Because it is a ground-breaking document that could pave the way for substantive negotiations toward a free trade agreement (FTA) (see August 15 post on APF’s survey of business attitudes to FTA negotiations), the study is worth closer examination.

The seven sectors include: natural resources – energy, forest products and mining – that together constitute over 1/3 of Canada’s total trade and 11.6% of GDP in 2011; agriculture and agri-foods; increasingly important clean energy and green technology; transportation infrastructure and aerospace; along with machinery and equipment R & D and manufacture, financial, engineering and other services, and textiles and apparel. I will focus on resources and agriculture in this post, other sectors in a second, and a summation of Canada-China trade in a third.

Natural Resources:

Now the world’s second-largest importer of natural resources and the largest energy consumer requiring oil and gas imports to meet over 50% of its needs, China is increasingly looking to Canada both as a source for imports and an investment destination. However, Canadian oil exports are severely restricted by the lack of pipeline infrastructure that has put the Northern Gateway project into the public spotlight.

Similarly, the bid for Calgary-based Nexen Inc. by state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) puts the Harper government’s embrace of foreign investment, particularly Chinese, in the face of negative public opinion, to the test. The study highlighted “the need for increased regulatory clarity, efficiency, and predictability in the context of direct investments in each other’s countries”.

Forest products, mainly lumber and wood pulp, have become Canada’s number one export to China, having expanded 45 fold within a decade to top $4 billion last year. In addition, Canadian companies are looking to higher value-added exports to satisfy China’s rising demand for products with low carbon footprints and using energy efficient materials. There is also upward demand for non-traditional products and by-products such as dissolving pulp, an affordable alternative to cotton. Going the other way, China is a major supplier of bamboo and rattan and certain forest products to Canada.

In mining, China’s massive manufacturing needs and rapidly improving middle-class living standards are fueling consumption of Canadian diamonds, gold, aluminum, iron ore, coal, nickel, potash, and other minerals along with Chinese outbound investment. Chinese investment in Canadian minerals has grown dramatically over recent years yet they amounted to only 1.8% of total FDI in Canada last year. For its part, Canada is interested in introducing Canadian junior mining exploration companies to China where no such industry exists.

Canadian natural resources related expertise and technology is coveted in China for aiding the sustainable development of natural resources. In energy, Canadian capabilities in long distance pipeline building would be a boon to China’s oil and gas infrastructure expansion. Canada’s green mining and deep exploration know-how and state-of-the-art mining technologies not only augment extraction rates and recovery ratios but also enhance land restoration and reclamation. There is plenty of space for cooperation in forest product technologies and forest management and protection practices as well.

Agriculture and Agri-foods

Barriers on both sides inhibit trade in this sector. Although China’s agricultural tariffs have been lowered since its 2001 WTO accession, they are still quite high at 15.6%. At the same time, Canada maintains average tariffs of 11.3% not to mention supply management in some industries. Moreover, different sanitary and phytosanitary measures, technical regulations and standards, and administrative capacity constraints often serve to delay, disrupt, or otherwise complicate trade between the two countries.

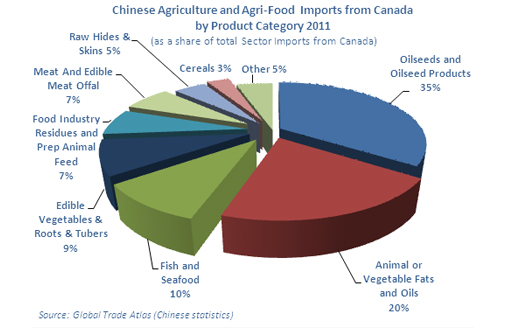

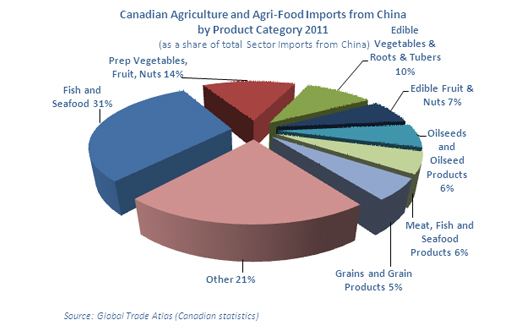

Despite these obstacles, China’s rapid urbanization and changing consumption patterns; its diversification of stable import sources to supplement domestic production; and consumer yearning for healthy and safe food products, particularly following the rash of food safety scandals, provide ample opportunities for Canadian agricultural producers and processors. Canada is the world’s leading producer of canola products and a major supplier of quality beef, pork, and fish and seafood while China is major supplier of prepared vegetables and fresh temperate-climate fruits to Canada.

On top of trade, Canada possesses considerable knowledge in agricultural water management, especially irrigation and drainage management and technology and low-till or no-till agronomic practices that can help China address soil deterioration and arable land loss. Canada is also a leader in animal husbandry, plant breeding, and plant and animal disease control that could lead to partnerships and investments in both countries.